-

Water-Moon Avalokitesvara

Hanging scroll, ink, colours and gold on silk. Goryeo Dynasty (935-1392), 14th century

The hanging scroll originated in a courtly context and depicts a scene from the Flower Garland Sutra in which a boy visits the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara on Mount Botarakga to ask him for instructions. The Bodhisattva turns towards him showing benevolence and compassion for the believer. Particularly noteworthy are the detailed depiction of the watery landscape at the foot of the rocky throne and the diaphanous veils.

Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Inv. Nr. A 09,59.

purchased by Adolf Fischer 1909 -

Pictoral ideograph of "honour" (yeomjado)

Unbekannter KünstlerHanging scroll, ink on paper. Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), 19th century

A peculiarity of Korean painting is the playful deployment of the eight written characters associated with the Confucian virtues. The integrated symbols emphazise the meaning of the ideographs, for example books symbolizing knowledge of the Confucian writings or the phoenix representing the upright character of a scholar-amateur.

Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Inv. Nr. A 77,108a u. A 77,109 b, donation from Kurt Brasch 1977

-

Horse and Two Grooms. Unknown artist

Hanging scroll, ink, colours, gold pigment on paper. Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), late 19th century

The painting shows a splendidly adorned pony and two horse-grooms. The expressive colours of the painting are astonishingly pure and executed using pigments which only became known at the end of the 19th century. The format and the exquisite workmanship are exceptional for the folk art of the Joseon Dynasty and do point to the fact, that the painting was executed for a special context.

Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Inv. Nr. A 77,79, donation from Kurt Brasch 1977

-

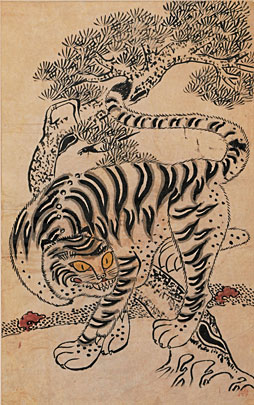

Tiger

Chong ChangHanging scroll, ink and colours on paper. Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), 18th/19th century

The tiger is both a guardian and a symbol for bravery and occupies a special place in Korean culture. In contrast to the brightly coloured depictions of folk art, this drawing in monochrome ink concentrates on the head of the animal with its expressive eyes and the gaping maw, while the rest of the body is only sketchily hinted at in the shape of the front paws, the forward portion of the back and the tip of the tail.

Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, Inv. Nr. 1996,53, in the possesion of the Stiftung für die Hamburger Kunstsammlungen, erworben im englischen Kunsthandel / purchased in the British art market in 1996

-

Shamanic painting

WitaeHanging scroll, colours on silk

The shamanic painting shows the guardian deity Witae up front, looking the observer straight in the eye. He is wearing a military helmet and presents a sword. He is the guardian of the Buddhist doctrine and was originally a Brahmanic deity. He can also become the helping spirit of a shaman but does not appear in rituals held for female clients.

Museum für Völkerkunde Hamburg, Inv. Nr. 79.40:21, from the collection of Cho Hung-youn, 1979

-

Shamanic painting

Sansin with TigerHanging scroll, colours on silk. Early 20th century

The indiginous Korean deity Sansin is one of the most significant guardian spirits of the shamans. He dispenses wealth and protects from illness, two of the most frequent wishes of female clients to the shamans. The normal iconographic canon of one or two accompanying "childlike attendants" is missing in this painting. Instead a Buddhist svastika can be found on the gourd, which is quite unusual.

Museum für Völkerkunde Hamburg, Inv. Nr. 80.20:1, aus der Sammlung Cho Hung-youn, purchased with funds provided by the Förderkreises des Museums für Völkerkunde Hamburg 1980

-

Shamanic painting

Sun and MoonHanging scroll, colours on plant fibre fabric

The two guardian deities Sun and Moon are dressed in wide robes and patterned red cloaks. Their heads are surrounded by halos, while their headdresses once showed symbols of Sun and Moon at present hardly recognizable because the material is badly worn. The inscription on the upper right side in Korean and Chinese repeats the identification of the deities, who are responsible for maintaining harmony between married couples.

Museum für Völkerkunde Hamburg, Inv. Nr. 80.20:5, aus der Sammlung Cho Hung-youn, erworben mit Mitteln des Förderkreises des Museums für Völkerkunde Hamburg 1980

-

Buddhist ritual painting

Unknown artistColoures on textile. Jejudo, 1930s

The Buddhist painting illustrates a Water-Land- Ritual, in which the Bodhisattva Ksitigarbha is invoked to help the deceased souls to escape from hell and ensure them of rebirth in the paradise of the Buddha Amitabha. The procedure of this ritual was exceptionally expensive so that the bereaved often just ordered a painting like this and brought sacrifices before it.

Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Inv. Nr. ID 45493, bought from a private collector 1990

-

Lidded long-necked bottle

Light-grey stoneware with engraved lotus decoration under celadon glaze. Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392), 1st half 12th century

Round-bodied bottles with a long neck were called crane-necked bottles and were probably used for pouring wine.

Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Inv. Nr. F 11,115, purchased by Adolf Fischer 1911

-

Wine jar in gourd form

Stoneware with celadon glaze and copper-red painted decoration. Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392), 1st half 13th century

The jar with its grey-green glaze is formed of two differently seized lotus-buds. At the neck of the jar there are two male figurines, holding lotus sprays in their hands.

Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, inv. Nr. 1910.166, purchased in Kyôto 1910

-

Boy attendant with phoenix

Wood, polychrome pigments. Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), 17th/18th century

The boy is holding an auspicious phoenix and can therefore be attributed to the sculptures of boy attendants who, since the later Joseon Dynasty, stand in the Halls of the Ten Kings of the Hell. These depictions of children lessened the fearsome power of the Kings of Hell and can be interpreted as a typical symbol of the later syncretistic Buddhism of Korea.

Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Inv. Nr. B 10,1, purchased by Adolf Fischer 1910

-

Jangseung (village guardian)

Wood, polychrome pigments. Incheon district, Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), c. 1895

Village guardians were erected in pairs at the entrance of the village during the jangseung ritual and were meant to guar-antee protection from disease and a good harvest. Male jangseung in the form of an official with hat represent the Sky God, while the female ones stand for the Earth Goddess. The inscription on this piece describes it as "the greatest general under heaven".

Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Inv. Nr. ID 16399, donation from Moritz Schanz 1897

-

Jangseung (village guardian)

Wood, polychrome pigments. Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), end of the 19th century

Jangseung were carved from a single tree-trunk and erected regularly in spring every one to three years. Only the arms, the hat brims and the rather unusual ears of this piece are attached. The inscription describes the location of the village and illustrates the practical function of the guardians as sign-posts.

Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Inv. Nr. ID 12214, donation from Max von Brandt 1890

-

Earrings

Gold. Period of the Three Kingdoms (57 B.C. – 668 A.D.), Silla, 5th – 6th century

The fragile earrings were probably made especially as burial objects for an aristocrat. They are made of finely rolled gold foil in hollow form.

Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe Hamburg, Inv. Nr. 1986.92, donation from Ryun Nam-koong 1986

-

Helmet

Brass, textile, fur and horsehair. Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), 19th century

Judging by its excellent workmanship, this helmet may have belonged to a high-ranking officer and was probably worn for official occasions.

Missionsmuseum St. Ottilien, Inv. Nr. K 2367

-

Set of garments formerly in the possession of Paul Georg von Möllendorff

Silk and other materials. Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), late 19th century

Paul Georg von Möllendorf (1847-1901) was in the service of the Korean Royal family from the end of 1882 till 1885 as an advisor in foreign affairs. The everyday clothing shown here date from that period, consisting of various garments which were worn in combination according to the degree of formality required and the season of the year.

Ethnologisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz Inv. Nr. ID 36671-36677

-

Daedongyeojido (Large map of the Eastern Kingdom)

Kim Jeong-ho (died about 1866)Woodblock print on paper; slipcase: paper, horn and cotton. Seoul, Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), 1861 or 1864

The Large map of the Eastern Kingdom consists of 23 individual sheets, of which one shows the city of Seoul and the rest the complete country of Korea and its offshore islands. Next to the symbols for administrative centres, garnisons etc., the most eye-catching elements are the mountain ranges, which run through the country. The map represents the zenith of East Asian cartography before it was superseded by Western methods.

Museum für Völkerkunde Hamburg, Inv. Nr. 12,24:138: from the collection of Carl Gottsche, Schenkung 1912