First Jewish Community in Cologne

Jews have probably lived in the province of Lower Germania since the end of the first century AD. By the fourth century they constituted a large and significant community.

In 321 Emperor Constantine the Great sent a letter to Cologne in which he assented to having Jews appointed to the Town Senate, the Curia. Only a large and well-off community was capable of providing members for such a municipal honorary position because in late Antiquity, members of the curia faced massive private financial burdens

The Question of Continuity

One of the most fascinating questions for researchers today concerns the fate of the Jewish community at the end of the Roman epoch.Did its members emigrate to the Mediterranean lands, more specifically Gaul, or did they continue to live in Cologne under Frankish rule, therewith constituting the nucleus of the great medieval community?

Medieval Community

The excavations proved that one the oldest synagogue north of the Alps known hitherto was situated in Cologne. It was dated back to a time in the first half of the 11th century.

The first reliable written evidence of the Jewish community, for the year 1075, is found in the Vitathe life of Saint Anno (II), Archbishop of Cologne. In an official document of 1091, the Annonis, Jewish Quarter is referred to as ‘inter iudeos'.

In 1096 the Jewish community is hit by the first massive persecution. Driven by their fanatic enthusiasm, crusaders kill Jews and destroy their living quarters on their march down the Rhine to the Holy Land.

Cologne's Synagogue is destroyed and Torah scrolls are ripped out and thrown into the mud on the streets. A number of Jewish residents are killed, while others find asylum with Christian acquaintances. However, when the archbishop orders the refugees to be evacuated to other places,´the crusaders eventually catch and murder them. In the course of the events, 300 Jewish inhabitants of Cologne are said to have been killed.

Nevertheless, it seems that it did not take long for the Jewish community to rally. In 1105/6 AD the surveillance of the new city gates and towers is delegated among the Sondergemeinden (parishes). Jews are allotted the supervision of the Judenpforte (Jewish Gate) at the corner of Kattenbug and Komodienstrasse and after the city was newly fortified in 1180, of the Judenwischhaus at the Turmchenswall.

Many Jews were long-distance traders and bankers, thereby taking on an important role in economic life that Christians were prohibited from exercising due to the church's ban on usury.

In the Middle Ages Jews operated under the special protection of the king. The Jewish treasure passed into the possession of the archbishop in the thirteenth century. Today the Jewish Privilege of Archbishop Engelbert II carved out in stone in 1266 can still be seen in the Kreuzkapelle (Chapel of the Cross) of Cologne Cathedral. The City Council, too, lay claim to the right to represent the Jewish citizens. In 1321 Cologne's first Book of Oath documents the legal regulations for Jews.

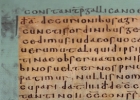

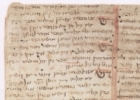

The Council of Jews was the most important committee of the Jewish community. It operated under the chairmanship of the so-called Jewish bishop (episcopus iudaeorum) and was in charge of administrative, legal and religious matters as well as of regulating contacts with outsiders. The Rabbinic Court that usually consisted of three members was an integral part of the Jewish Council. In those days, Cologne's scholars ranked among the German elite. Close contacts were cultivated with educational centres on the Iberian Peninsula. Rabbi Asher Ben Jehiel (or Rosh) from Cologne, for example, was appointed High Rabbi of Toledo in 1303. Some of the most magnificent Hebraic manuscripts of the Middle Ages were created in the scriptorium of Cologne's synagogue community.

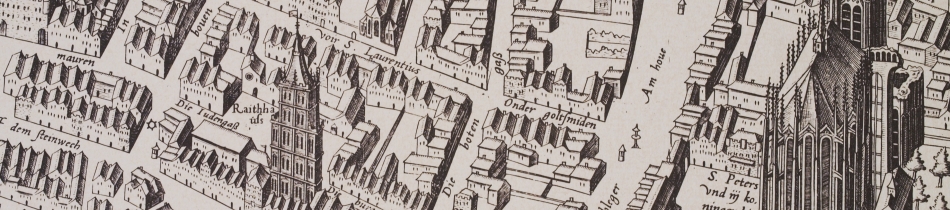

Buildings of the Jewish Quarter

In its heyday, Cologne's Jewish community comprised 800 -1000 members. The Jewish district extended from the Budengassestreet in the north to Oben Marspforten in the south and from the street "Unter Goldschmied" in the west to the Town Hall in the east.

Around 1135 the Judenschreinsbuch (Jewish real-estate record) was set up, making it possible to synchronise the excavation results with the written sources.

Synagogue

The excavations led to various individual findings in regard to the building phases and interior of the Synagogue. This is how it became possible to reconstruct what the Bimah, the most important element of the Synagogue next to the Torah shrine, would have looked like, from finds of more than 350 fragments to date. The Bimah, also referred to as the Almemar, was the reading pulpit at the centre of the Synagogue. It was crowned by a series of finials, surrounded by column clusters with floral capitals and provided with multi-cusped arches in which birds and small animals gambolled in wine leaves. The Bimah was presumably created around 1280 by French craftsmen from the Cologne Cathedral lodge, making the Bimah a unique testimony to the peaceful cohabitation of Jews and Christians in the city at that time.

This masterpiece of Gothic minor architecture was shattered into pieces during the Pogrom of 1349. The iron components were pulled out and the cellar below the Bimah pedestal filled with the broken stonework.

Mikveh

In 1956, the roughly17-metre-deep shaft of the Mikveh, the Jewish ritual bath, was excavated. The Mikveh is located in the very heart of the Jewish Quarter directly south of the Synagogue. Today it can be seen under the silver pyramid in the Town Hall Square. In order to conserve and restore the Mikveh, it was necessary to cover the former glass roof construction.

According to the ritual requirements, a Mikveh has to hold ‘living' water. In the case of the Mikveh in Cologne, this means flowing groundwater. To this day, the changing level of the Rhine can be read at the bottom of the Mikveh from the differing water levels there. At the end of 2009, the level of water carried by the Rhine was so low that the Mikveh was completely dried out. This incident enabled the extraction of samples for scientific examinations and a detailed construction record that will clarify the individual building phases of the Mikveh more precisely. It has already been detected that, like the synagogue, the Mikveh dates back to the 11th century: like other monuments, it shows earthquake damage in early building phases.

Further Buildings

A Jewish house that was first mentioned in 1135 was identified at the western end of the Synagogue. The hospital is another prominent building of the Jewish Quarter. It functioned as a communal and charitable social institution for the sick, the elderly and for pilgrims. Its archaeological remains can be seen in the Portico. Next to the hospital, parts of the domus Lyvermann, the bakery and the warm pool are preserved and together form a very unique building ensemble in Europe.

The Pogrom of 1349 and the Final Persecution of the Jews in 1424

The excavations brought about new scientific conclusions about the Pogrom of 1349: Finds rescued from the cesspit allotted to the rabbi's lodging on the upper floor of the Synagogue date from a time shortly after August 1349 and give a unique insight into the way of life of a Jewish family. Not only the immense abundance of animal bones, but also botanic remains, mirror eating habits that adhered to strict Jewish dietary laws. It has also been possible to obtain detailed information on household goods. The finds range from book clasps to the remains of burnt parchment with Hebrew writing, from toys to medicine bottles, from window glazing to metal furniture mountings and from stove tiles to roof covering. These were thrown into the cesspit after the Synagogue had been plundered.

On the instigation of the new archbishop Friedrich von Saarwerden, the Council gave permission in 1372 for Jewish families to settle again in Cologne. However, already in 1423, the City voted against the prolongation of the edict to protect Jews and their settlement in Cologne. In 1424 all Jewish families had to leave the city.

The Fate of Cologne’s Jews in the Modern Era

After the Jews had been expelled from Cologne in 1424, many Jewish families established their settlements on the opposite bank of the Rhine, in Deutz and Muhlheim. During the daytime, Jewish doctors were permitted to visit their patients in Cologne and Jewish merchants to carry on with their commercial transactions. After the suppression of the leading large-scale Jewish community in the Rhineland, the Jews living in the Electorate of Cologne reorganised. This included the appointment of a state Rabbi. During the era of Absolutism, Jewish families again ascended to become court factors. They served as purveyors or as bankers to the princes. As a result of the occupation of the Rhineland by French revolutionary troops and the incorporation of the area west of the Rhine into the French state, all groups were granted freedom of religion and settlement. Eventually in 1798, the first Jewish family moved back to Cologne. From then on, the Jewish community established itself again in Cologne and expanded to several thousand members. The composer Jacques Offenbach and the banker Salomon Oppenheim are prominent examples. However, the cultic centre of Jewish life was no longer located at the Town Hall. A synagogue now stood in Glockengasse on the grounds of what is known today as the "Offenbachplatz". It was funded by the Oppenheim family and built by the cathedral master-builder Zwirner in 1857-61.

By 1925, Cologne's Jewish population had risen to approximately 20 000 people. The persecution of the Jews by the Nazi-regime virtually wiped out the entire Jewish community. 11 000 people of Cologne's Jewish community were deported and murdered. Today about 5000 Jewish fellow citizens live in Cologne again.

Further information

NS Dokumentationszentrum / Museum of the history of National Socialism in Cologne:

http://www.museenkoeln.de/homepage/default.asp?s=172

Kolnisches Stadtmuseum (Cologne City Museum):