Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst

All thoughts are concentrated on one thing, our museum idea. It still seems bold to seek to place East Asian art on a level with European art, and there is still no museum in Europe dedicated to this art. We are seeking to go along untrodden paths. (...). We have formed an overview of what Europe possesses in the way of East Asian art. We know the museums and private collections in London and Paris, we have studied those in Frankfurt, Munich, Leipzig, Dresden, Vienna and Berlin (…). Nowhere, though, has any attempt been made to provide a unified picture of East Asian art as a whole, or to present it in its phases of development. But this is our endeavour. Painting and sculpture, those two pillars of the visual arts, will lead; the others, the so-called applied arts will follow. (…) We shall not erect a princely palace for this art, but rather a quiet, elegant treasure-house which will itself be silent while letting the works of art speak. Our plan provides for no prestigious exhibition rooms or pompous staircases, but silent rooms, inviting visitors to immerse themselves in the art. (…) We shall approach the City of Cologne with a project that is ready to implement. We are united to Cologne with bonds of friendship, and we believe it is the right place for our work, Cologne, the busy metropolis of the west [of Germany] with connections in all directions, its soil seeped in ancient culture, nourishing a rich intellectual culture alongside its business culture. It was the collecting activities of art-loving men that made Cologne into the important museum city which it is. Their example has inspired us to add the East to the West.

Fischer, F. (2), 178 f.

This was how, in her diary, published in 1942, Frieda Fischer described the hopeful expectations which led in 1909 to the foundation of the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst, the Museum of East Asian Art, in Cologne.

In actual fact the path that Adolf Fischer (1856–1914) and his wife Frieda (1874–1945) had to tread in order to realize this goal was not at all so smooth and uncomplicated as one might deduce from the diary. After negotiations in Berlin and Kiel, it was in Cologne that the Fischers found the conditions that enabled them to implement their life’s work, the foundation of a museum for East Asian art. The institution was able to open its doors already in 1913. It was the first museum in Europe specifically dedicated to the art of the Far East. It differed from existing museums in presenting not just individual genres, but sought to convey a comprehensive view of the multiplicity of forms and periods of East Asian art.

Adolf Fischer was born in Vienna in 1856 as the second of three sons and three daughters of an industrial magnate. An unpublished curriculum vitae of Adolf Fischer dating from 1901 informs us that after completing his education at a boarding school in Zurich, he was forced to join one of his father’s businesses. His “artistic soul” got into such great conflict with the career planned for him that at last he managed to enforce the realization of his wishes in spite of all the opposition. He took drama lessons from the Viennese court actor Josef Lewinsky (1835–1907). In 1887 Fischer took part in a theatrical tour of the USA, but the life on the stage was so bad for his nerves that he abandoned his acting career on medical advice. Fischer withdrew for a number of years to Italy, where he devoted himself to the study of Italian art; he also went on two trips to Egypt. After that, he lived in Munich and Berlin, preparing for a journey round the world. This took him in 1892 for the first time to Japan, whose art made a profound impression upon him; he felt that this was “the axis around which my life would turn”. Fischer, F. (2), 178 f.

Instead of returning to Vienna, in 1896 Adolf Fischer settled as an amateur scholar in Berlin, where in his flat on Nollendorfplatz, the so-called “Nollendorfeum”, he created an impressive display of the objects he had acquired hitherto.

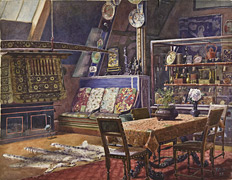

left: Wada Eisaku: Nollendorfeum, water colour, 44.2 x 57 cm, 1899, Museum of East Asian Art Cologne (A 252). right: Wada Eisaku (1874-1959): Staircase to the Nollendorfeum, the apartment of Adolf and Frieda Fischer at the Nollendorfplatz in Berlin, water colour, 50.4 x 42.6 cm, 1899, Museum of East Asian Art Cologne (A 251)

Fischer’s private life took a decisive turn at the end of 1896. On Christmas Day he held a flat-warming party to which he invited the Goethe scholar Erich Schmidt (1853–1913) and his family, asking him to bring along the 22-year-old industrialist’s daughter Frieda Bartdorff, whom he had met at Schmidt’s house. Frieda Bartdorff had been trained as a grammar-school teacher. She was impressed by the Nollendorfeum and even more by its occupier, who was 18 years older than her. The next day, they got engaged, and they were married on 1 March 1897.

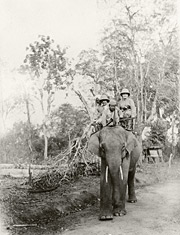

Adolf and Frieda Fischer’s honeymoon took them in September 1897 via Vienna, Ahmedabad, Hong Kong to Japan, Formosa and back to Japan.

left: Wedding photograph of Adolf and Frieda Fischer, 1897. center: Frieda Fischer in the Nollendorfeum, c. 1901.

right: Frieda Fischer riding in a rikscha in Tokyo, 1898

In May 1899 the Fischers returned to Berlin, having acquired numerous art-works which they had barely unpacked before sending them to Vienna. On January and February 1900 the sixth exhibition of the Viennese Secession took place.

The Viennese exhibition of the Fischer collection did not go down particularly well with the public, but artists and intellectuals were enthusiastic. For the first time, the Fischer collection had experienced the light of a public viewing, providing Fischer the private collector with the chance to gather experience in the planning and implementation of exhibitions.

Evidently the Secession exhibition triggered in Adolf and Frieda Fischer the desire for a specific new beginning. On 8 April 1901 she noted in her Chinese journal:

A great turning-point in our lives: we have presented our collection to the Prussian state, which will transfer it to the Völkerkundemuseum in Berlin, and have thus dissolved our Nollendorfeum. We wish to be free and independent and find our way to a life that serves not only our hobbies, but strives also for general cultural goals.

Liberated from their possessions, the Fischers set off via London on their next expedition to Asia, which took them via Burma to Japan and China. A diary entry reveals that it was in the summer of 1902 that Adolf and Frieda Fischer first forged plans for the foundation of a museum “that would not serve ethnographic purposes, but would be dedicated solely to the art of East Asia”.

Following the belated foundation of the German Reich in 1871, the country pursued, as part of its colonial policy in the Far East, the goal of catching up with Britain and France. While relations following the conclusion of Prussia’s treaty with Japan in 1861 and the Unequal Treaty with China the same year were determined largely by economic considerations, the accession of Kaiser Wilhelm II and the dismissal of Bismarck in 1890 ushered in a momentous change. The focus of foreign policy now shifted from “great-power politics in Europe” to “world-power politics”.

German colonial policy formed the framework within which scholarly occupation with the language, literature, history, philosophy, religion, art and culture of the East Asian countries enjoyed an enormous upsurge. Most of those who were academically involved with East Asia did not share the sentiment of the imperialist polemics, treating the object of their research with unprejudiced objectivity and respect. Even so, they did not fundamentally question the aims and methods of imperialism.

Against the background of German colonial interests, voices were also raised in favour of a “Reich Museum of Asian Art”.

The accusation that German colonial policy had not taken any account, when Jiaozhou was occupied, of the interests of German museums had its effect. The Reich government saw itself obliged to take measures to promote expertise in the area of East Asian art and the East Asian art industry. In 1904 the post of Academic Specialist was created at the Beijing embassy. It went first to Adolf Fischer, and then to Ernst Grosse, who held it from 1904 to 1907 and from 1908 to 1912 respectively. Just as Britain and France transferred important examples of world art, in particular from the countries they had colonized, to the British Museum or the Victoria & Albert Museum in London and the Louvre in Paris, it was primarily the Berlin museums that were to reflect Germany’s geopolitical successes.

Adolf Fischer did not hesitate to accept this appointment, which did him great honour. But first, he was concerned to obtain permission to collect, at his own expense, works for the museum of East Asian art which he was planning in Kiel. This was granted, on the one condition that the chests containing the artworks acquired for Kiel first be sent to the Völkerkundemuseum in Berlin. The Völkerkundemuseum was to have the right of “first refusal”, a solution with which Fischer had no problems, for the remit of the Völkerkundemuseum was to acquire ethnological and “religious-scientific objects“ and “excellent copies of classical works”, but not art.

Plans for the building of a museum of East Asian art in Kiel were already well advanced, and the artworks acquired for the museum by Fischer in Japan, China and Korea were already in storage in Kiel, where he had been offered a gymnasium as a temporary home for his collections in April 1908. When it became clear, however, that the city of Kiel would be in no position to fund the building and maintenance of the museum in a fitting manner, Fischer revoked the contract in 1909.

On 21 June 1909, with the signing of the contract to found a museum of East Asian art in Cologne, the wheel had turned full circle for Adolf and Frieda Fischer.

Adolf and Frieda Fischer’s journeys can be almost completely reconstructed on the basis of the hand-written diaries. All in all, they spent some ten years in the Far East. Fischer, who, like many of his contemporaries had come via Japan and Japonisme to recognize the overwhelming importance of the art of China and Korea, had to assemble the jigsaw puzzle of the art-history of the Far East for himself. He could only do this by travelling, seeing as much as possible, reading as much as possible and taking what advantage he could of private collections and museums.

As soon as word got round that Fischer had arrived in town, his hotel room was besieged by dealers offering him their wares, often on commission, and agreeing viewing dates with him. Above all in Japan, Fischer was glad to have sculptures and paintings which had interested him on his visits to dealers brought to his hotel. While the dealers sometimes complained and protested, mostly they complied. Once the object was in his keeping, Fischer went off to the national museums in Kyoto and Nara to look for comparable items. In addition, Fischer asked the sculptor and restorer Tanaka Monya to cast, with him, a close and critical eye on potential purchases.

Fischer also learned interesting techniques of determining whether bronzes were genuine. Fischer wrote: We returned to his (…) reception room, where he showed me four bronzes (…). Some seemed very questionable to me, especially one which looked as if it were coated in malachite (…). I sniffed it, but I couldn’t detect any smell of lacquer. Sumitomo then lit various matches, which he held to the bronze, so that if a coat of lacquer had been present, it would certainly have melted and run. But after we had wiped away the smoke and dirt, the patina shone in new splendour. Sumitomo also applied ammonia, but apart from the dirt, none of the green patina was removed. This test provided, at a time when fakers were less sophisticated than they are today, fairly certain proof that the patina was genuinely due to aging.

Cologne city council commissioned the architect Franz Brantzky (1871–1945) who had designed the extension to the Kunstgewerbemuseum for the Museum Schnütgen, which was completed in 1908. As the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst was conceived as part of this complex, it seemed an obvious choice to get him to prepare the design, in order to achieve a uniform Neo-classical building that would look self-contained from the outside. The foundation stone was laid on 24 January 1911.

This art centre on the Hansaring was destroyed in the Second World War; apart from a fragment of the old city wall on Gereonswall and the name of a street, Adolf Fischer Strasse, there is nothing left to recall it.

The interior design of the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst in Cologne was, as far as is known, the first public commission undertaken by Josef Frank (1885–1967), who was just 27 at the time.

The plans show a T-shaped building complex, which was accessible via a corridor from the Kunstgewerbemuseum. A total of 32 exhibition rooms are grouped on three storeys around a central staircase. The room layout on the ground floor is marked by an alternation of larger suites of rooms and smaller cabinets or “niches”, in which smaller objects or rooms fitted with tatami mats in the Japanese style are presented. In order to make optimum use of daylight, the cabinets are always set up at right angles to the windows, projecting into the room. Reflections in the glass are kept to a minimum by the fact that the light falls from the side, and is muted by light gauze curtains. Frank developed various types of cabinets, including pyramidal ones and others for horizontal scrolls with oblique panes, to ensure an optimum view of the exhibits without disturbing reflections.

left: Staircase. center: Presentation of Buddhist sculptures; the light coming from the side reduces the reflection of the glass cases.

right: Display case with Chinese handscroll and additional case on top for the display of ceramic figurines

For another reason too, the rigorously pursued room-filling presentation was a novelty: it challenged visitors to become active themselves and move around the objects, instead of being led along cabinets placed monotonously and erratically along the walls. The room concept developed by Josef Frank enabled visitors to see three-dimensional objects in the round. In addition, it provided for a great deal of variation in the rooms, so that the eye always had something different to focus on. The special apparatus for the presentation of Japanese coloured wood-block prints also followed the ideal of the active, self-determined visitor. The prints were in narrow frames behind glass and could be turned about their own axis by means of a bar on the floor. This allowed the visitor a thematically and chronologically ordered view from close up.

The building of the first German Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst (Museum of East Asian Art) was destroyed during one of the last air raids on Cologne in the Second World War. The largely evacuated collections were undamaged apart from the Inrô and Netsuke Collection comprising roughly 900 objects.

It was not until 1951 that the museum again had a well-qualified director in Werner Speiser (1908-1965). In spite of all the difficulties and vicissitudes of the postwar period he succeeded in organising exhibitions of East Asian art and ensuring that the Cologne museum did not fall into oblivion. His successor, Roger Goepper (born 1925), was responsible from 1966 onwards for the planning of the new museum building. Thus, the new building of the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst on the Aachener Weiher was officially opened 33 years after the destruction of the original building on the Hansaring. Since then the museum has acquired an international reputation with important special exhibitions.

left: Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Japanischer Innenhofgarten (Gestaltung: Masayuki Nagare). © Foto: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln (Marion Mennicken) . center: Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst Köln, Außenaufnahme vom Aachener Weiher aus. © Foto: Rainer Gärtner, Köln. right: Raumaufnahme Chinesisches Gelehrtenzimmer. © Foto: Lothar Schnepf, Köln

The new museum was built in 1977 according to plans by the Japanese architect Kunio Maekawa (1905-1986) and is one of the most important architectural monuments of the postwar period in Cologne. Maekawa, a pupil of Le Corbusier, is regarded in Japan as the founder of modernism. In the Cologne building he unites traditional Japanese architecture with a modern formal vocabulary. The low rectangular blocks and cubes of the museum building are grouped around the Japanese landscape garden designed by Masayuki Nagare. Nagare, who is well-known in the West as a sculptor and achieved international fame with his works in the USA, also created the sculpture entitled “Fahne im Wind” (flag in the wind) for the Cologne museum. It was installed on a specially created island in the Aachener Weiher directly in front of the cafeteria.

“Clean, open and austere”, or “clean, open and substantial”: this description could also be applied to the lives of Adolf and Frieda Fischer. They made the compilation of the collection and the establishment of the museum their life’s work, to which both of them were totally committed. They deserve our gratitude.

The museum, though not its building, survived two world wars and, following the bombing in 1944, was re-housed in a new building designed by Kunio Maekawa in 1977. Under the directors who succeeded Frieda Fischer (1876-1945), Werner Speiser (1908–1965) and Roger Goepper (b. 1925), who started their work in 1951 and 1966 respectively, the collections were extended into areas hitherto underrepresented, and greatly enriched. In this connexion, the donation of archaic Chinese ritual bronzes and Chinese Ming furniture by Hans-Jürgen von Lochow, the Japanese painting from the estate of Kurt Brasch and finally the purchase of Hans Wilhelm Siegel’s collection of early Chinese pottery deserve particular mention. More recently, the museum has been enriched by the purchase of Heinz Götze’s collection of Chinese and Japanese calligraphy, and the permanent loans from the collection of Peter and Irene Ludwig.

The intellectual openness, the generosity, the courage and the charisma of Adolf and Frieda Fischer, and not least their discipline, their stamina and their ambition, form the foundation on which the Museum für Ostasiatische Kunst has built. May the museum in Cologne serve future generations as an ambassador and mediator, waking in them an understanding and enthusiasm for the world’s one art.